The Christmas story contains a challenging message for organisations and their leaders on fundamental issues like control, power, knowledge and status.

The gospels contain the familiar tale of how Mary is visited by the angel Gabriel and, as foretold, subsequently becomes pregnant. She and Joseph travel to Bethlehem in order to comply with the conditions for the Emperor’s census. There is no room for them in the inn and so the baby (destined to be the king of kings) is born in a stable. Angels appear to the shepherds proclaiming peace and the shepherds visit the baby – followed a little later by an unknown number of sages from the east with gifts. Herod gets wind of a special royal birth and, fearing a rival, resolves to kill all the children under two in and around Bethlehem. But the parents are forewarned in a dream and flee to Egypt. Thus begins God’s programme to save the world.

Out of the four gospels only Matthew and Luke include accounts of Jesus’ birth. They use these accounts to introduce all the big themes of the gospels as a whole. This includes a lot with implications for concepts that play a big part in organisational life. These are ideas that have always been somewhat counter-cultural, even through the years of Christendom, rarely fully embraced by the church let alone by anyone else. Nevertheless, the claim is that this is how things really are. What does the story have to say?

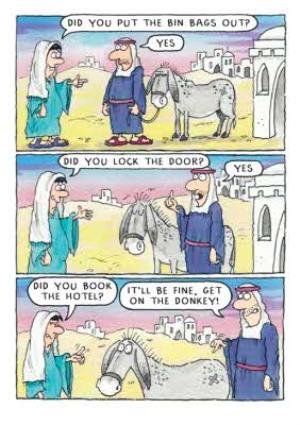

A concept much cherished in organisations is that of control. It is associated usually with the idea of efficiency. But there is not a lot of control or efficiency in the Christmas story. In fact there doesn’t appear to be much of a plan at all. Mary (who shouldn’t be pregnant anyway) and Joseph set out for Bethlehem without even having booked their accommodation: the stable is a last minute desperation option. The wise men are following, not a map or a guide book, but a star. They do not know where it is going and find themselves at the court of the wrong king on the way – precipitating Herod’s vicious reaction. At the everyday level, the thing is a bit of a mess. But it is one in which larger forces are at work and an event of cosmic importance plays out through apparently disparate and chaotic events.

Managers see their role as exercising as much control over the organisational process as possible. And, at one level, that is quite right. No-one wants to buy something or receive a service from an organisation that doesn’t produce what it says it will when it says it will and to an agreed standard or work for one that doesn’t pay wages accurately and on time. At that level control is possible and desirable. But at the higher level life is unpredictable and unmanageable. At that level control is an illusion. Tomorrow is uncertain. People do not do what they are told or do not see the world as you do. But it is possible to develop an understanding of the organisational values and strategy, to create a larger, shared narrative which provides, not control, but a basis for creative and enriching responses to the ebb and flow of life.

Power is a concept also much valued in organisational life. In the nativity story, the person with the greatest and most obvious earthly power is Herod – and he misuses it spectacularly. The magi are, presumably, powerful men in their own country, but in the story they are far from home. The shepherds, Mary and Joseph, they all have no power. And at the centre of the story is a baby – who is, it becomes clear later, God incarnate. This is a story in which the heroes do not possess or divest themselves of power, and of a God who chooses not to act by the exercise of power but to enter the world quietly. And yet (whether you approve of the fact or not!) this story also changed the world.

In organisations power is a reality and position or personality or the possession of resources gives more of it to some than others. Pretending this is not so serves no-one. The issue is how we will use it. Will we impose ourselves and our ideas on others or will we use power to help others flourish and to realise the gifts and contributions of those who have less power? The latter is, I suggest, far more likely to have a transformative effect.

The story also tells us something interesting about another organisational notion – knowledge. It is, of course, closely related to the notion of power. In organisations today knowledge is highly valued. We all want data – whether it is formal data about the organisation and its performance or informal data about its politics. In fact, knowledge is frequently hoarded rather than shared absolutely because to possess it is to possess power and to make oneself important. But this is a story about the limitations of knowledge so conceived. The wise men, the magi, know something and humbly journey to seek a fuller understanding of something they do not completely comprehend. But the revelation comes to the most ordinary people in the story. The moral? Knowledge is found in the most unexpected places, perhaps even amongst those who are closest to the work! And those who possess a lot of data and theoretical knowledge need to exercise that knowledge with some humility.

Finally, another related idea. Status. Status matters in organisations and there are obvious signs of it in office accommodation, car parking places and the cars themselves. But here is a story that overturns our concepts of status. The wise men become learners, the shepherds (a rascally crowd according to historical accounts of the period) become courtiers. A young woman becomes the mother of God and God becomes a baby. All organisations are bound to divide tasks according to some sort of essentially hierarchical structure. But these are, or should be, distinctions of role rather than status. The CEO has a job to do that no-one else can do – to take an overview of performance and lead on the creation of an organisation fit for tomorrow, perhaps. Some people will have skills which make them more important to organisational success than others. But there should be a fundamental equality. This is how things are in the eyes of God who did not consider his own status something to cling to, let alone remind everyone of on every possible occasion. And the best organisations value everyone, recognising that everyone has a role to play and that a sense of common cause is crucial to success.

Happy Christmas, one and all, and may an excessive concern for control, power, knowledge and status give way to creativity, space for others, humility and common cause in 2020.

Hey, like this post? Why not share it with a buddy?

Tweet

Great post Keith. I have never thought about the Christmas story in quite this way, and how relevant and important the messages our to day to day work.